Dieterich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) was most likely born in Helsingborg, Denmark, to German father Hans and (possibly Danish) mother Helle. He grew up in nearby Helsingør, where Hans was parish organist at St. Olai’s, the grand basilica. As a twelve-year-old boy, Buxtehude witnessed a major repair of St. Olai’s organ, a first step toward his own life as a master of the instrument. He also received musical instruction as part of the liberal arts curriculum of Helsingør’s Lutheran Latin school, from principles of music theory, to composition, to singing in choirs for Danish and German-speaking churches. Choirs in such schools typically met for an hour at noon each day, sang in polyphony (sometimes door-to-door on the eves of feast days), and were available to perform at weddings and funerals. The brother of Hans Leo Hassler (composer of “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded”) put together an anthology of pieces that young Buxtehude sang, and the same anthology was later purchased by J. S. Bach for use in the Thomas School in Leipzig.

When his studies in Helsingør were complete, Buxtehude found an apprenticeship with an organist either in Copenhagen or Hamburg. In late 1657 or early 1658, he traced the footsteps of his father and took positions as organist first in Helsingborg, then in Helsingør. Both cities were suffering significantly from a war between Denmark and Sweden, and Buxtehude had to make himself content with poor living conditions, a meager salary, and the results of foreign occupation and economic decline. Nevertheless, Buxtehude managed to make himself known as an organ expert by the age of 25, and as a mark of this he was invited to inspect and repair Helsingborg’s organ. A leading music scholar, Marcus Meibom, happened to be attending St. Mary’s at Helsingør while Buxtehude was there, giving Buxtehude opportunity for even further learning.

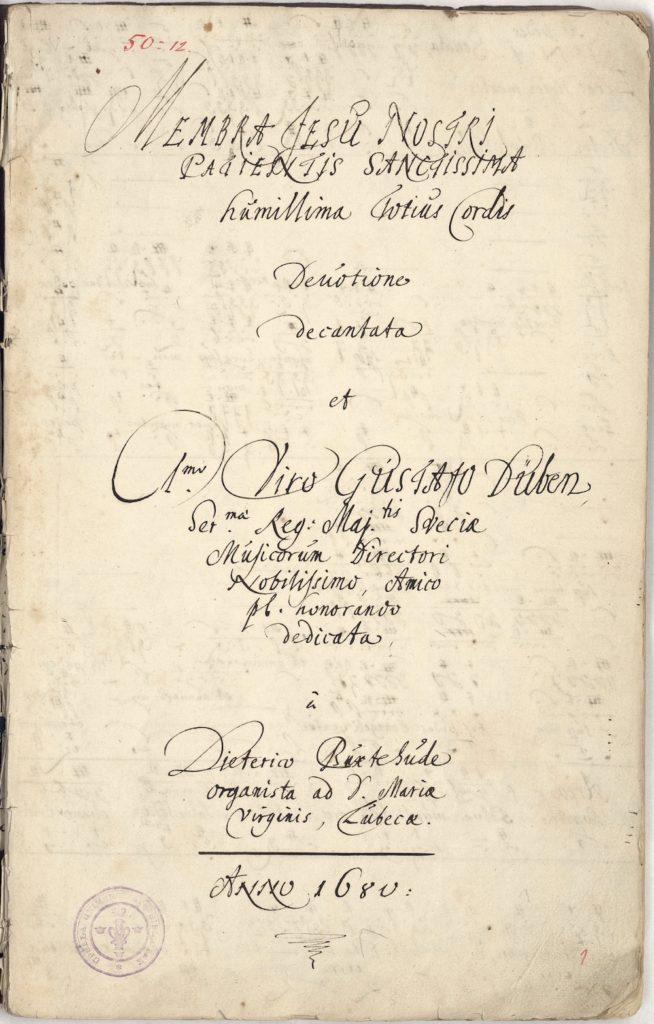

In 1668, following the death of Franz Tunder, Buxtehude took the position of organist in Lübeck, where he would remain for almost forty years. Lübeck was a thoroughly Lutheran city. According to one disgruntled visitor in the 1670s, in “inconsiderate zeal… their Lutheran Ministers…had persuaded the Magistrates to banish all Roman Catholics, Calvinists, Jews, and all that dissented from them in matter of Religion, even the English Company too.” All four religious superintendents in Lübeck during Buxtehude’s lifetime were staunch orthodox Lutherans who shunned the encroachments of Pietism. The same observer above also noted, “The people here spend much time in their Churches at devotion, which consists chiefly in singing.” Buxtehude’s parish, another St. Mary’s, boasted the center of the city’s skyline.

At age 31, Buxtehude married Franz Tunder’s second daughter, Anna Margaretha, fulfilling the common expectation that a new candidate would care for his predecessor’s kin. In less than a year’s time, the couple had both baptized and buried their first daughter, Helena. Of their six other daughters, two died in early childhood, one in young adulthood, and three survived their father. Much of Buxtehude’s extended family also lived in Lübeck, including his widowed mother-in-law, whom he generously provided for; his brother-in-law Samuel Franck, who worked closely with him as the cantor at St. Mary’s; and eventually his own father Hans, who remained there until his death in 1674. Buxtehude dedicated a piece of funeral music to his father, titled Fried und Freudenreiche Hinfahrt, or “Peaceful and Joyful Departure”—for, he wrote, his father “departed with peace and joy from this anxious and unpeaceful world…and was taken home by his Redeemer (for whom he had long waited with yearning).”

Perhaps the most illustrious feature of musical life in Lübeck was the Abendmusiken, an five-part series of evening concerts performed annually at St. Mary’s on the last two Sundays of the church year and the first three Sundays of Advent. This endeavor was entirely voluntary labor on the part of Buxtehude—it was not included in his official duties. Buxtehude composed the music, raised the funds, and of course conducted the performances for Abendmusiken, which were typically dramatic oratorios expounding on a biblical theme and often aligning with the time of the church year. For instance, an oratorio titled The Wedding of the Lamb included biblical texts about the wise and foolish virgins, familiar chorales such as “Wachet auf” (“Wake, Awake, for Night is Flying”), and new poetry sung in a duet between Christ and the Church.

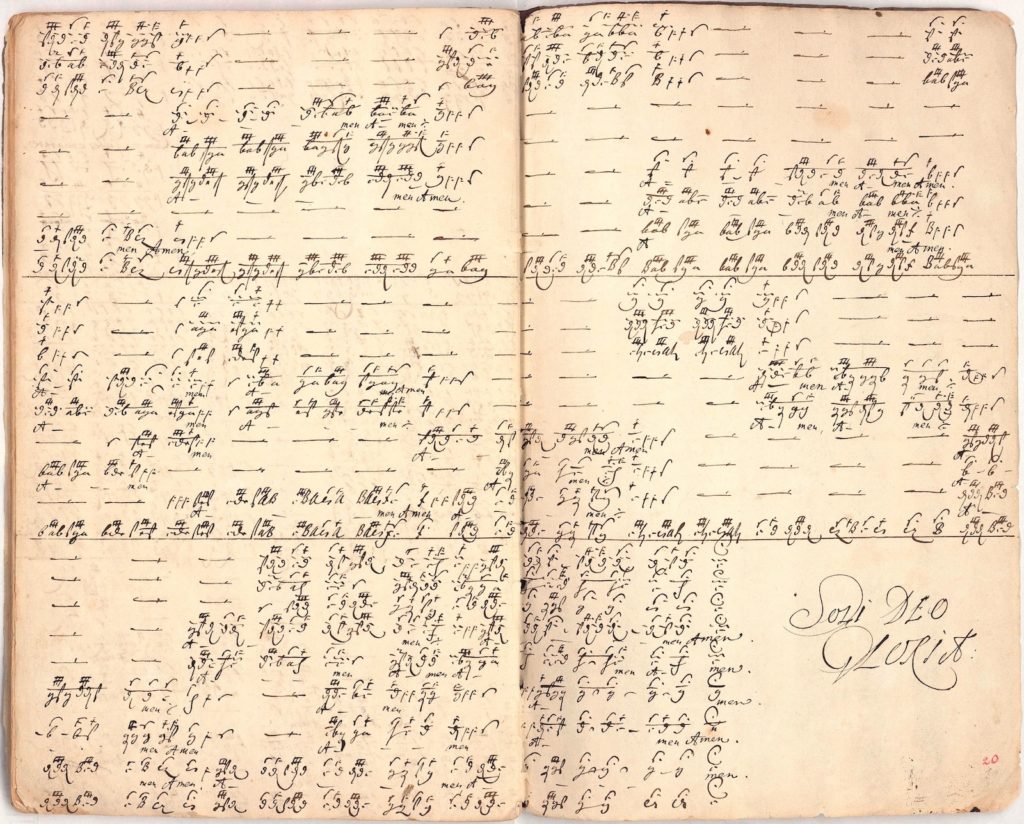

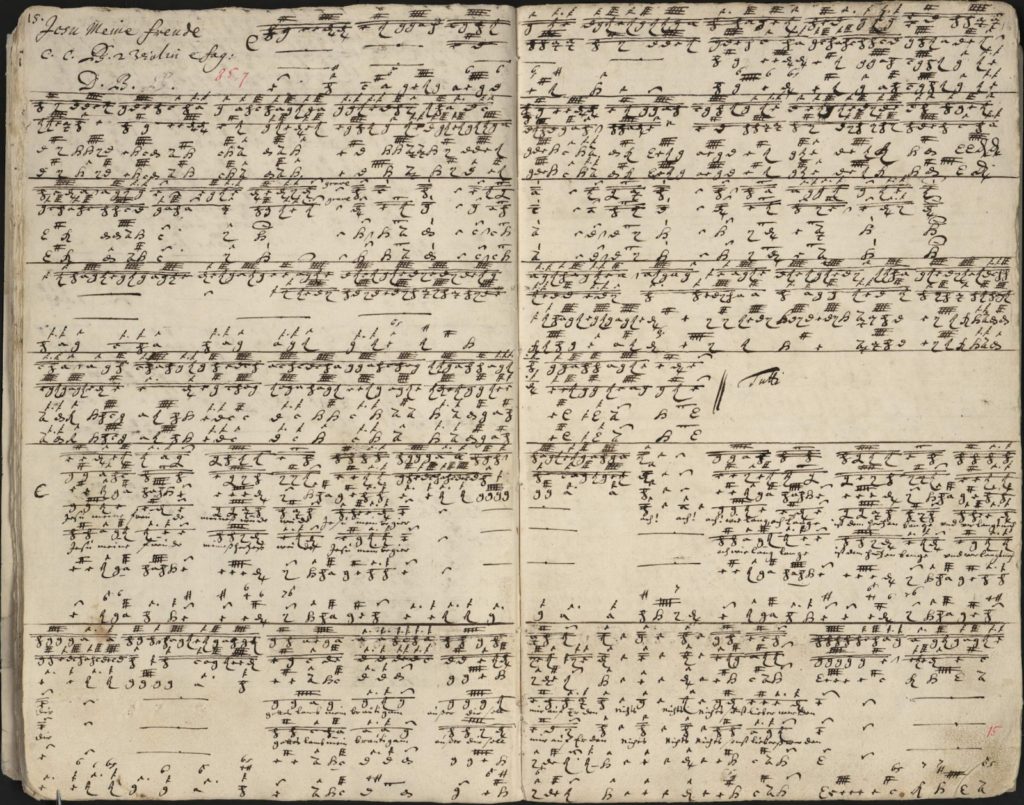

Outside the city of Lübeck, Buxtehude was known primarily as an organist. He composed around 137 keyboard works, which were frequently copied and studied by others. Johann Pachelbel once wrote to Buxtehude expressing interest in sending his thirteen-year-old son to study under him. Johann Sebastian Bach made his famous journey on foot to Lübeck to hear Buxtehude perform: After quadrupling his permitted time away from work, Bach returned to Arnstadt with a greater knowledge of the organ, as well as inspiration for his future arrangements of Christ lag in Todes Banden (BWV 4) and Jesu meine Freude (BWV 227). One of Buxtehude’s great supporters commented that “in the ardor of his compositions, Buxtehude understood well how to give a foretaste of heavenly bliss.”

Source: Dietrich Buxtehude: Organist in Lubeck by Kerala J. Snyder.

Arrangements by Dieterich Buxtehude

A Mighty Fortress Is Our God (SWV 143)

“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” (Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott), text by Martin Luther (1529). Setting by Heinrich Schütz (1628, SWV 143). Homophonic, SATB.

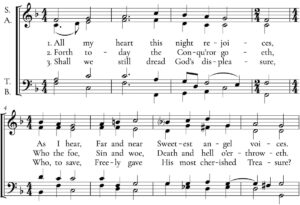

All My Heart This Night Rejoices

“All My Heart This Night Rejoices” (Fröhlich soll mein Herze springen), text by Paul Gerhardt (1653). Tune by Johann Crüger (1653). Setting by Johann Crüger (1653). Homophonic, SATB.

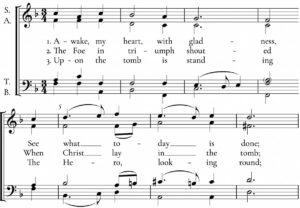

Awake, My Heart, with Gladness (BWV 441)

“Awake, My Heart, with Gladness” (Auf, auf, mein Herz, mit Freuden), text by Paul Gerhardt (1647). Tune by Johann Crüger (1648). Chorale setting by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 441 variant). Homophonic, SATB.

Awake, My Heart, with Gladness (Crüger)

“Awake, My Heart, with Gladness” (Auf, auf, mein Herz, mit Freuden), text by Paul Gerhardt (1647). Tune by Johann Crüger (1648). Setting by Johann Crüger (1649). Homophonic, SATB.

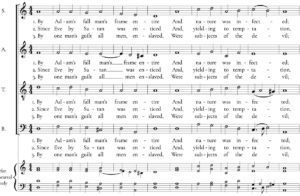

By Adam’s Fall Man’s Frame Entire

“By Adam’s Fall Man’s Frame Entire” (Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt), text by Lazarus Spengler (1524). Setting by Johann Crüger (1649). Homophonic, SATB.

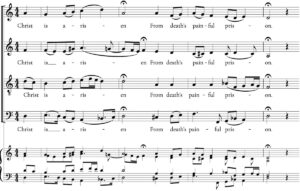

Christ Is Arisen (BWV 276)

“Christ Is Arisen” (Christ ist erstanden), text anonymous (c.1150). Tune traditional Austrian (c.1000-1500). Chorale setting by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 276). Homophonic, SATB.