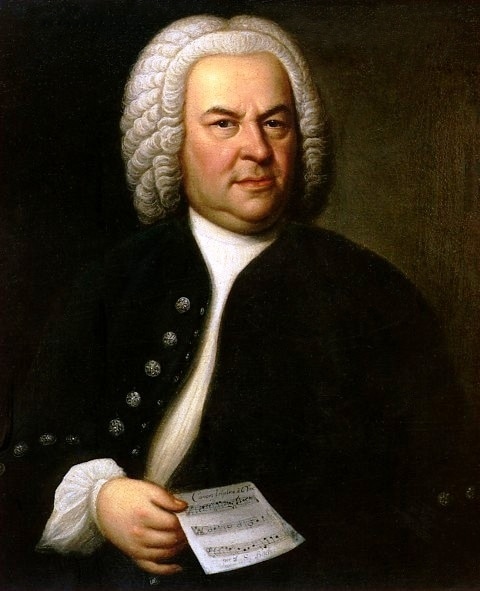

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in 1685 in Eisenach, Germany. His large extended family was teeming with musicians, including cantors, organists, and town musicians. The family was close-knit and held a jovial reunion once a year to entertain themselves with their own music. Bach’s own father was the town musician in Eisenach. Bach was orphaned, however, before he was ten years old, and in 1695 he moved to Ordruff to live with his older brother Johann Christoph. Here he received his first clavier lessons. Bach quickly mastered any easy pieces his brother put in front of him, and when Christoph refused to let him use a book of more difficult compositions, including works by Buxtehude and Pachelbel, Bach secretly slipped the book from a latticed cupboard and began to copy the pieces by moonlight. After six months, when he finally finished the painstaking project, his brother caught him and confiscated the copies.

Christoph died in 1700, and Bach traveled with a schoolmate to St. Michael’s School in Lüneburg where he sang in the boys’ choir. Before long, however, he lost his treble voice and committed himself instead to improving his skills on the clavier and organ. When he was 18, Bach became the town musician in Weimar and then at Arnstadt. He was driven by a vigorous dedication to master the organ. Bach even walked over 250 miles to Lübeck to hear the famous Buxtehude play, and he stayed there for several months to learn everything he could.

As his proficiency on the organ became more widely known, Bach was offered several organ positions, and in 1707 he accepted a job at Mülhausen. Here he also married his first wife, Maria Barbara, with whom he had seven children. Just a year later, Bach changed positions again and became court organist and eventually chapel master at Weimar. By age 32, Bach was matchless on the organ. He composed avidly, usually at night, and learned to play his new work the next day. He could improvise on a given subject continuously for over two hours. When some nobility arranged a contest between Bach and a renowned French organist named Marchand, the Frenchman was afraid to show up and went home. Bach also had a keen knowledge of organ construction, and whenever he tested an instrument—after first pulling out all its stops to see if it had “good lungs”—he proved to be a strict but fair judge.

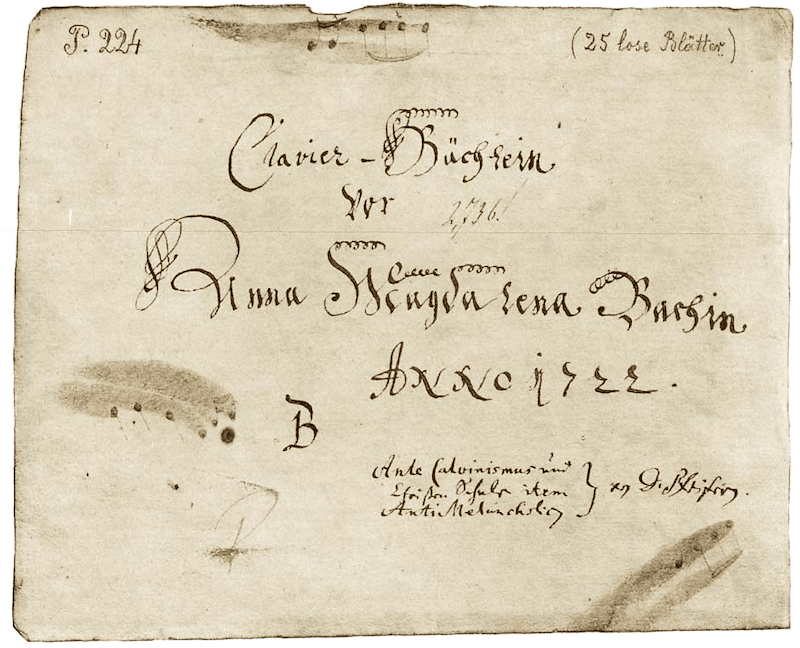

Bach left Weimar in 1717 to take up a position as chapel master for Prince Leopold at Cöthen. (Because he so forcefully pressed to be dismissed from his post in Weimar, he spent that November in jail!) Himself a harpsichordist, Leopold loved and knew music well, and Bach enjoyed six years composing and playing in his service. Because Leopold was a Calvinist and opposed music in church, Bach composed many secular works during his time in Cöthen, including the familiar Brandenburg Concertos (1721) and the Little Clavier Book (1722).

While away on a trip with Leopold’s court in 1720, Bach received word that Maria had died. About a year later he married Anna Magdalena, a soprano vocalist who often helped Bach copy music and became the mother of his thirteen other children. Their home was hospitable and welcoming to visitors, especially music-lovers. Bach was a caring father and saw to it that his children had a good education. Several of his sons, including William Friedemann Bach and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, became excellent musicians in their own right.

Bach’s biographer, Johann Forkel, wrote the following about Bach’s contentedness at home:

“Bach did not make what is called a brilliant success in this world. He had, on the one hand, a lucrative office, but he had, on the other, a great number of children to maintain and to educate from the income of it. He neither had nor sought other resources. He was too much occupied with this business and his art to think of pursuing those ways which, perhaps for a man like him, especially in his times, would have led to a gold mine. If he had thought fit to travel, he would (as even one of his enemies has said) have drawn upon himself the admiration of the whole world. But he loved a quiet domestic life, constant and uninterrupted occupation with his art, and was, as we have said of his ancestors, a man of few wants.”

Bach took his final position in 1731, when he moved to Leipzig to be an instructor at the St. Thomas School. Here he taught voice lessons, conducted four boys’ choirs, and organized and led the playing of music in the four Lutheran churches in Leipzig. Every Sunday, his musicians and choirs—drawn from the school, town musicians, and sometimes university students—performed a cantata in one of the churches, usually preceding the sermon. Bach oversaw the musical life of Leipzig outside the Divine Service as well. He directed a rotating choir to perform in hospitals and a house of correction, and he also composed music for midweek services, funerals, and evening performances at the popular Zimmerman’s coffeehouse. He was often visited by admiring musicians, and was once all but forced by the delighted King of Poland to give him a concert and test out his pianoforte collection.

As Bach aged, his eyesight weakened, and after several unsuccessful surgeries he became effectively blind. He died at age 66, having composed some of his most famous works while in Leipzig, including the Goldberg Variations (1741 or 42) and the Mass in B minor (1733).

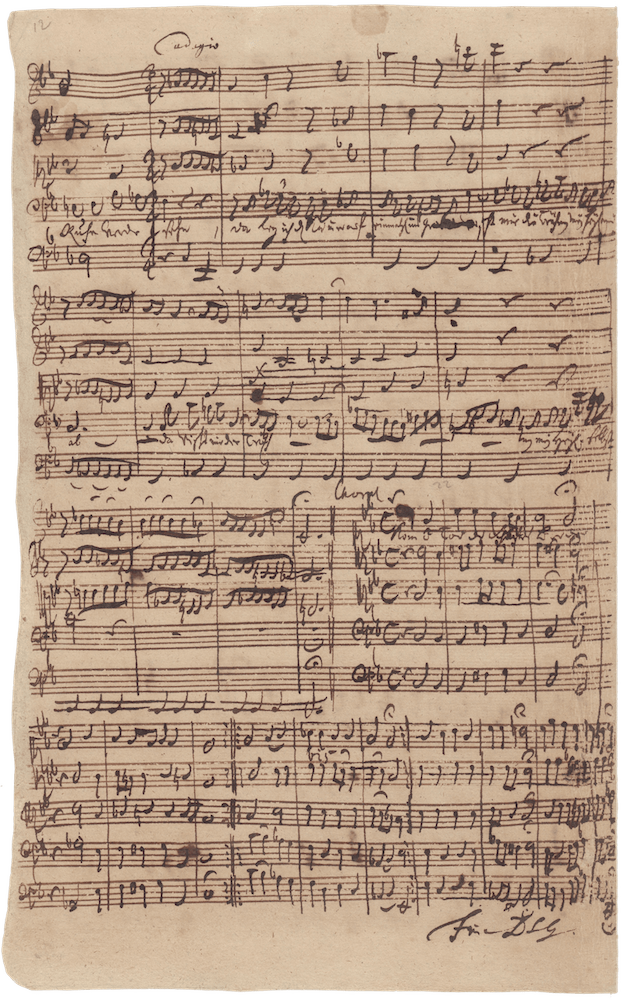

Bach was certainly a prolific composer. He wrote for the clavier, organ, violin, and cello, and of course for the voice, including five sets of cantatas for the Church year, five passions, and many oratorios, masses, Magnificats, and motets. His four-part chorales, according to his son Carl Philipp Emanuel, were distinguished by the “quite special arrangement of the harmony and the natural flow of the inner voices and the bass.” He diligently studied and learned from the great composers that preceded him. Once, when asked how he became such a great composer, Bach replied, “I was obliged to be industrious; whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well.”

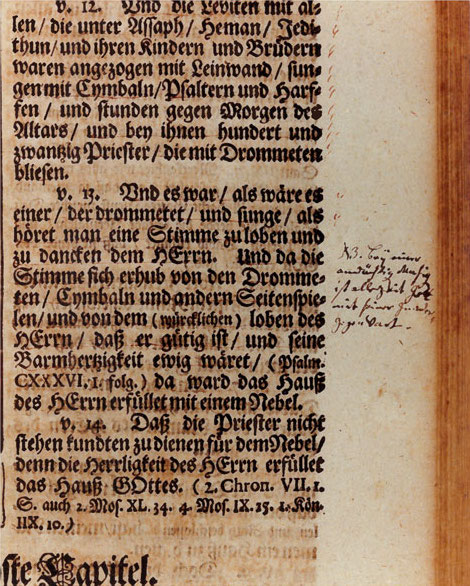

Bach was a devout Lutheran, and it is clear that his Christian faith informed his work as a musician. In his personal, annotated copy of Abraham Calov’s edition of the Lutheran Bible, Bach wrote alongside 1 Chronicles 26 that King David’s establishment of music in the temple “is the true foundation for all church music that is pleasing to God.” Later, next to chapter 29, he added that the passage was “a splendid example that, besides other forms of worship, music especially has also been ordered by God’s Spirit through David.” For Bach, music in worship was nothing short of an institution of God.

Bach’s steadfast Lutheran faith is shown elsewhere in his manual on figured bass, as explained by author Günther Stiller:

“That Johann Sebastian Bach in his thinking and acting very consciously stood on the foundation of the orthodox Lutheran doctrine of faith, a foundation laid in his childhood and youth, is made clear in his course in figured bass. This must be considered a well-thought-out and therefore basic statement of Bach’s, one that he dictated to his students. In its second chapter, which deals with ‘Definition,’ we read:

‘The figured bass is the most perfect foundation of music. It is played with both hands in this way, that the left hand plays the notes prescribed, but the right hand adds consonances and dissonances so that a sweet-sounding harmony may result to the glory of God and for an allowable delight of the heart. And as in the case of all music, so also the purpose and final goal of the figured bass should be nothing else but only the glory of God and the restoration of the heart. Where this is not observed, there you have no real music, only devilish bleating and harping.’….

“Bach again makes use of a formulation that tends in the same direction in his dedication of the Orgelbüchlein, namely, the confession that witnesses anew to his Lutheran stance of faith: ‘In praise of the Almighty’s Will, And for my Neighbor’s Greater Skill.’ Here, too, the ‘final purpose’ of all composing and music making is summarized in the double purpose: Glory to God and service to the neighbor.”

Sources: “On Johann Sebastian Bach’s Life, Genius, and Works” by Johann Nicklaus Forkel in The New Bach Reader, ed. Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel (quote from page 451); Johann Sebastian Bach and Liturgical Life in Leipzig by Günther Stiller (quotes from pages 208 and 210); “Biography of J. S. Bach” by Michael and Lawrence Sartorius at baroquemusic.org (accessed 1/2/23).

Arrangements by Johann Sebastian Bach

Awake, My Heart, with Gladness (BWV 441)

“Awake, My Heart, with Gladness” (Auf, auf, mein Herz, mit Freuden), text by Paul Gerhardt (1647). Tune by Johann Crüger (1648). Chorale setting by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 441 variant). Homophonic, SATB.

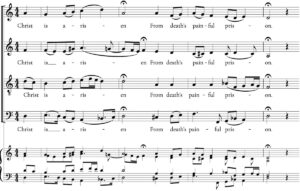

Christ Is Arisen (BWV 276)

“Christ Is Arisen” (Christ ist erstanden), text anonymous (c.1150). Tune traditional Austrian (c.1000-1500). Chorale setting by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 276). Homophonic, SATB.

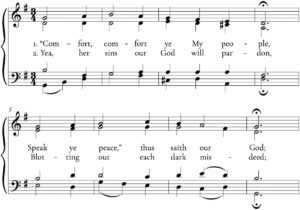

Comfort, Comfort Ye My People (BWV 70.7)

“Comfort, Comfort Ye My People” (Tröstet, tröstet meine Lieben), text by Johann Olearius (1671). Chorale setting by Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 70.7), originally for text Freu dich sehr. Homophonic, SATB.