Michael Praetorius was born in 1571 in Creuzburg, Germany. His father was a Lutheran pastor who was often persecuted for his faithful confession, especially against the compromising Philippist Lutherans. The family moved to Torgau, where Praetorius began his studies under Michael Voigt, the successor to the first Lutheran cantor, Johann Walther. At school, Praetorius learned to sing hymns and motets in the choristry. He also began composing pieces of his own.

At the death of his parents, Praetorius moved to live with his oldest sister Maria, and then with his brother Andreas, who was a pastor in Frankfurt. When Praetorius was about sixteen, Andreas died. The church in Frankfurt gave Praetorius pay and housing to serve as their organist, and for awhile he continued his studies at the university, planning to eventually become a pastor. At age nineteen, he chose to leave these studies and instead become an organist for Duke Heinrich Julius in Wolfenbuttel. Regarding this decision, Praetorius later wrote, “Never in my life have I aspired to great honor and dignities; at the time when I became an organist, I could have easily become a great doctor, but it has always been better for me to live in fear and humility than in honor and distinction.” After his death, Praetorius’s pastor stated that he had “greatly desired to pursue that profession [of pastor], and he often regretted the fact that he did not devote himself to the public ministry.”

For the next twenty years, Praetorius served as chamber organist and eventually court music director for Duke Julius. Besides playing organ in the chapel, he arranged for music at meals and recreation, composed pieces for festivals, and taught music to the duke’s children. While in Wolfenbuttel, he also met and married Anna Wernighof, with whom he had two sons.

Praetorius treasured the organ as an instrument that aided the responsive nature of the liturgy. “It is a very lovely and pleasant thing to hear,” he said, “when the entire assembly joins in together with the choir and organ like this, and shows and portrays to some extent what it’s going to be like in heaven when all the dear angels and saints of God intone and take up the Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus and Gloria in Excelsis Deo.” Praetorius knew how to build and maintain organs, and he wrote his own manual on organ construction and repair.

Praetorius’s strong Lutheran confession is evident throughout his compositions. He published fifteen installments of sacred music, titled Musae Sionae or Muses of Zion, in which he modified Latin works to be doctrinally sound and arranged an abundance of Lutheran hymns. He wrote for various numbers of voices, so that choirs of any size could use his work. He carefully chose which phrases to repeat in a given piece, depending on which theological point should be emphasized. Even in his secular work, such as the dances in his collection called Terpsichore, Praetoruis’s design was to give listeners enjoyment and rest with decency, separate from the music of pagan worship.

After Duke Julius died, Praetorius continued his work in Wolfenbuttel, but he also traveled as a nonresident music director in other German cities. In Halle, he met Samuel Scheidt, and in Dresden, he collaborated for a time with Heinrich Schütz. He published another series of sacred music titled Polyhymnia, consisting largely of concerti for festivals of the church year. His use of multiple choirs and groups of instruments in a performance, stationed in different places within the room, astounded and moved his listeners. Before he completed his vast aspirations for the Polyhymnia project, Praetorius died at age forty-nine and was buried beneath the organ at Wolfenbuttel.

In a dedication to a collection of choral music for ordinary congregations, Praetorius explains the purpose of music: to proclaim God’s Word, and to move the human heart to love that Word. He wrote,

“God the Lord has placed the knowledge of musical harmony in human hearts and has always had his divine doctrine and the glory of his holy name recorded in songs, thereby prompting worship to be rendered to him, primarily for these two reasons: First, that his holy Church might all the more joyfully and gladly proclaim his grace and truth and praise and honor him with spirit and mouth. To do so ‘is a precious thing’ (Psalm 92:1). And secondly, that the doctrine about the true God and all divine exhortations, comfort, praise, and thanksgiving contained in the psalms and in harmonious settings might be that much more easily and deeply inculcated in hearts, so that they might be kindled and roused to the burning zeal of true godliness. For since the Holy Spirit has seen that the human heart is difficult to bend toward godliness and virtue, while being all too greatly inclined to sensuality, he has blended God’s commands with the loveliness and pleasure of melody, so that together with its sweetness the knowledge and praise of God and of all Christian virtues might be poured into their hearts.”

In the back of each installment of Polyhymnia, Praetorius included a prayer, and each one shows evidence of his deep Christian piety. In the third installment, for example, he wrote:

“O Lord Jesus Christ, the eternal sweetness and song of those who love Thee, the salvation and lover of penitent sinners, by whose grace I am what I am [1 Cor. 15:10], by whose mercy I live, move, and subsist [Ac. 17:28]: O sweetest Jesus, grant me comfort and patience in every time of my tribulation, especially in the straits of my death. Hide me in the holes of Thy wounds from the face of Thy anger until Thy fury passes by, O Lord [Ex. 33:22-23]. Strengthen me to resist the devil, the world, flesh and blood, that dead to the world, I may live to Thee alone. And in the final hour of my departure, receive my spirit as it returns to Thee, and lead me into eternal joys. Amen.”

Source, including quotations: Heaven is My Fatherland: The Life and Work of Michael Praetorius by Siegfried Vogelsӓnger, trans. Nathaniel J. Biebert. Final prayer translated by Pastor Andrew Richard.

Arrangements by Michael Praetorius

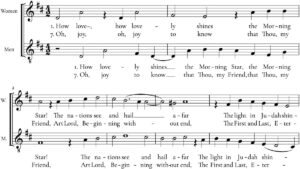

How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, á 2

“How Lovely Shines the Morning Star” (Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern), text by Philipp Nicolai (1597). Tune by Philipp Nicolai (1599). Setting by Michael Praetorius (1610). Polyphonic, ST.

How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, á 5

“How Lovely Shines the Morning Star” (Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern), text by Philipp Nicolai (1597). Tune by Philipp Nicolai (1599). Setting by Michael Praetorius (1610). Polyphonic, SATTB.

Hymn for All Hours

“Hymn for All Hours” (Hymnus Omnis Horae), text by Aurelius Clemens Prudentius (348-c.413). Tune traditional Latin. Setting by Michael Praetorius (Hymnodia Sionia 28, 1611). Polyphonic, SATB.

Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming

“Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming” (Es ist ein Ros entsprungen), text German (16th cent.). Tune and setting by Michael Praetorius. Homophonic, SATB.

Lord, Keep Us Steadfast in Your Word

“Lord, Keep Us Steadfast in Your Word” (Erhalt uns, Herr), text by Martin Luther. Setting by Michael Praetorius. Polyphonic, SAB.

Rejoice, Rejoice, Believers

“Rejoice, Rejoice, Believers” (Ermuntert euch, ihr Frommen), text by Laurentius Laurenti (c. 1700). Tune (Freut euch, ihr lieben Christen) by Leonhart Schröter (1587). Setting by Michael Praetorius (1609). Homophonic, SATB.